A short walk from the Croatian

parliament is the Museum of Broken Relationships. Zagreb’s quirkiest museum

displays countless artefacts donated by couples from around the world symbolizing

the end of their love. The results of Sunday’s elections to the European Parliament

may make the long-standing political parties in Croatia and their voters

suitable for exhibition.

Croatian party politics has been

dominated for much of the past two and half decades by the Croatian Democratic

Union (HDZ) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Recent polls, however,

suggest that the combined vote for these two parties has dropped from nearly

80% in 2007 to under 60%. Still a significant figure, it nonetheless underlines

changes in the party system and highlights phenomena that we have witnessed

across Central and Eastern Europe, and are beginning to see in Western Europe

as well.

For almost two decades, Croatia’s

political party system remained stable and relatively straightforward. Goran Cular

and Nenad Zakosek’s research on voters’ attitudes finds a longstanding and

coherent divide: on one side stood nationally and religiously orientated

parties, led by the HDZ, which also expressed a slight preference for markets,

on the other side were parties led by SDP, which tended to downplay national

and religious themes and were more sceptical of market forces. The former group

dominated the 1990s, but from the turn of the century the two groups habitually

rotated in government. These overall divisions remained relatively stable even

as the nationally orientated HDZ shifted its orientation towards embracing EU

accession.

Things have changed since the

late 2000s. The longstanding parties have lost support from voters – especially

younger voters - who see them not just as too entrenched in their focus on past

conflicts, but also as tainted by clientelistic relationships. The waning

affection for the existing parties was highlighted in the 2011 elections by the

entrance into parliament of the Croatian Labourists – the Party of Labour. The new entrant drew support from both the Social

Democrats and sections of the blue-collar HDZ vote. Although the Labour Party has

now lost some of its support, its voters have not returned to their original

electoral homes. Indeed, all factions

in the current parliament have seen large parts of their electorates tempted by

the emergence of new political forces, thanks in no small part to the governing

Social Democrats’ lacklustre management of the economy, leadership struggles within

the HDZ, and a series of high profile corruption scandals in both these leading

parties.

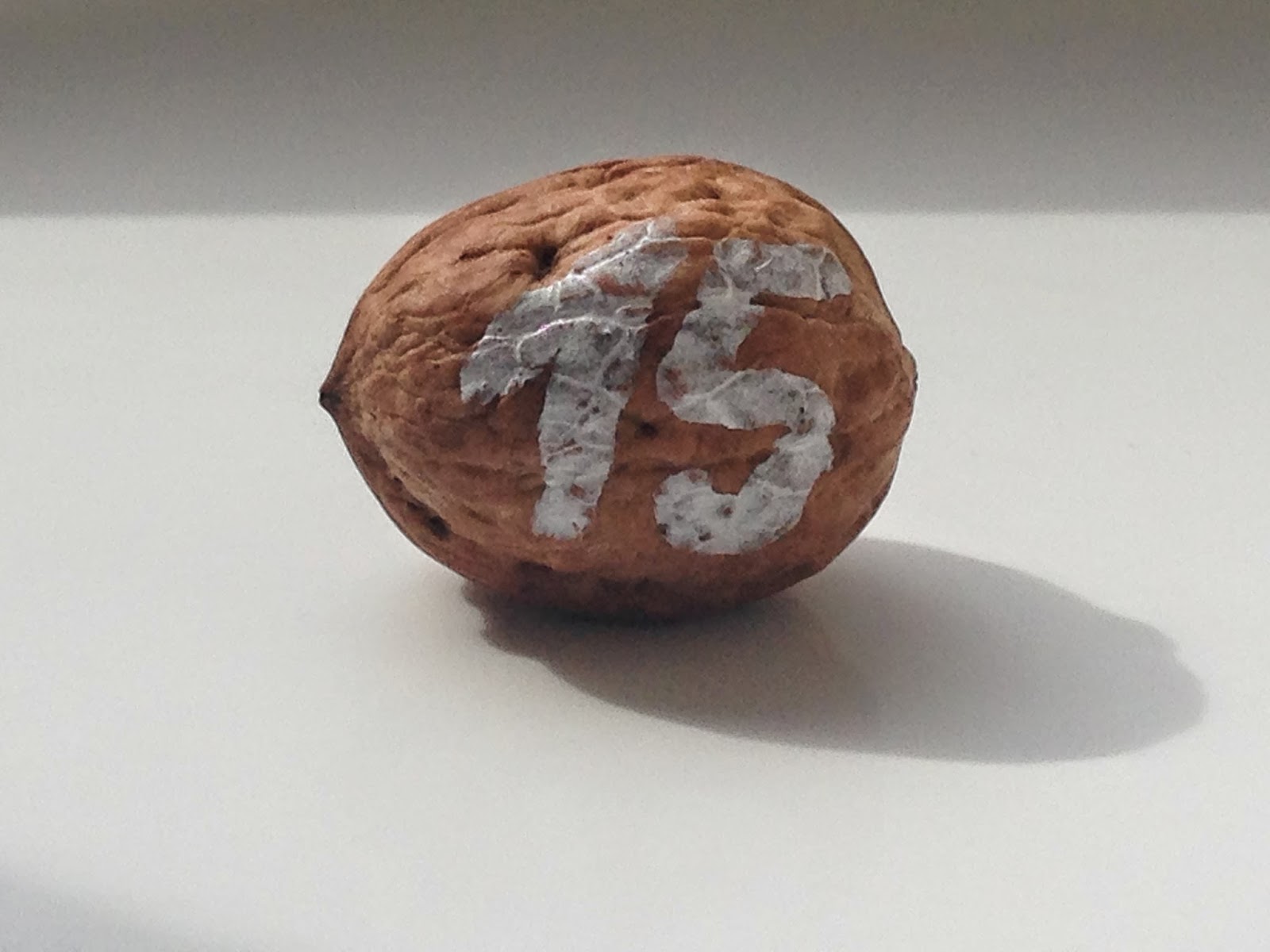

One of the most prominent new parties

is Orah (‘walnut’ in Croatian), which

is running at above 10% in the polls and looks set to win at least one of

Croatia’s eleven seats in the European Parliament.

Orah’s appeal is based on the

popularity of its leader, Mirela Holy, a former SDP government minister who

fell out with Prime Minister Zoran Milanovic. The party mixes an

anti-establishment novelty appeal with a market-friendly ‘green’ agenda

reminiscent of that promoted by Greens in Estonia and the Czech Republic. Orah - whose full name translates as ‘Sustainable

Development for Croatia’ - seems particularly appealing to the sensitivities of

younger voters; success in the European elections may offer Holy’s party a chance

to solidify its position on the party political scene.

In other countries in Central and

Eastern Europe, such new entrants have been known to fade before they have the

chance to compete in more than one election: indeed, appeals based around

novelty tend to lose their power rather rapidly. As

we have argued elsewhere, the key to longevity lies in becoming and

remaining the standard bearer on one of the main issue divides of programmatic

competition and having a well-developed party organization. Social media can

galvanize and mobilize some voters, but parties that endure need to combine clicks

and mortar: a network of party

offices and members remains indispensible for long-term success.

It is unwise to read too much into

the results of European parliament elections, but as the cases of Slovakia and Slovenia

are likely to highlight, they are, more often than not, rehearsals for

forthcoming national elections: new parties can use such elections as a way of

building up their profile, demonstrating their dynamism, and forging

relationships with voters. On Sunday, some Croatian voters will cast their

ballots for Orah; the challenge will be to persuade voters to choose it again

in subsequent elections. Otherwise, the

Museum of Broken Relationships might see a walnut on display alongside the symbols

of Croatia’s older parties.

No comments:

Post a Comment